Reflecting on Loss, Healthcare, and the Urgent Need to Expand Medicaid

Dec 11, 2023

In November, State of the South held its fourth convening in Birmingham, Alabama. Meeting over lunch, community members, nonprofit leaders, business owners, policymakers, and artists gathered to discuss the benefits of and barriers to closing the health insurance coverage gap in Alabama.

Following the event, we invited panelists and participants to reflect on their experiences. We’re honored to share with you this reflection from Jenny Fine.

Reflecting on Loss, Healthcare, and the Urgent Need to Expand Medicaid

On the morning of July 6, 2022, as I begin most days, I called my mother to check-in. Upon her hello, I started asking questions about items mentioned in the church bulletin. She stopped me mid-sentence with, “Oh, Jennifer, we have other things to talk about right now. Beth passed away in her sleep last night.” I hung up the phone and told my ninety-two-year-old grandmother who I live with as a caregiver. I’ve never seen her cry, but as these words – “Beth’s dead” – left my lips, she collapsed onto the softness of her brown velvet floral loveseat. “My Beth?!” she exclaimed, looking up at me. I nodded yes. We both let out a long wail, a moaning from the gut as if we had been simultaneously sucker punched in the stomach. For the first time in my life, I saw Granny cry.

Rushing out the door, I remembered just two years earlier when I got a similar call. In May of 2020, Gerald, Beth’s husband, died of a massive heart attack while driving to work. It was a Saturday morning and leaving in a rush, he left his wallet behind. It wasn’t until that evening that Beth got the news from my aunt, whose hand-me-down truck Gerald had been driving. I slept next to my older sister for two weeks following her husband’s death. It was the first time in thirty years our bodies lay together in sleep’s tenderness and vulnerability. But Beth didn’t sleep.

When we were in elementary school, Beth and I shared a room. After Mom tucked us in, we would wait for the light under the doorway to dim and sneak into the same bed. Laying side-by-side as if spooning, but not so close, we would roll from side to side tracing messages with our fingers on each other’s backs. Dragging my finger across her spine, we spoke in secret, each message ending with the scrawler wiping the text from our backs, a corporeal chalkboard. Our secret night conversations always ended with an ‘I, L, O, V, E, U.’

Two months after Gerald died, Beth lost her full-time job as a property manager for a local rental company, and she started losing weight. Three months later, she learned that her lease on the “friends and family discounted” rental house she and her three boys lived in would no longer be a rental property. They would have to move. By this time, Beth was not her highly organized self. She was the kind of woman who loved to make a list and was eager to check each item off. But now, she was not motivated to do anything but sleep outside of work, so everyone in the family pitched in to help pack. She found a new job that paid $13/hour with no benefits other than her boss’ generous discount on the management company’s monthly rent for the property on Yellowleaf Dr. She found a new home, literally and figuratively, at work. We moved the boxes to her new rental, but she never unpacked them.

Since Gerald’s death, Beth had been exhausted. If she wasn’t working or feeding her boys she was sleeping. I’m not fully clear on when Beth sought medical help, but I know that she called me three times during the last year of her life to say that she had made an appointment with a primary care physician. Each time during the scheduling call, Beth’s insurance (Medicaid) would be preapproved and the appointment scheduled. As a new patient, the wait was often long, sometimes months, and each time, the day before the appointment, the doctor’s office would call to check Beth in and collect her insurance information for payment. Each time, Beth provided the office with the same preapproved Medicaid insurance information. Each time, contrary to her previous call, she was told that their office didn’t take Medicaid and her appointment was immediately canceled. None of the offices offered her direction on who takes Medicaid or where to go for help before hanging up.

A month before Beth died, she was driving home from work and was T-boned by an uninsured driver and totaled her car. A week later, she called me from work in tears, 80 pounds lighter in weight, but carrying the weight of ten thousand worlds. She said, “Children and life never stop wanting even when you feel like you are dying”. Every morning she washed and curled her hair, put on makeup, and tried to present her withering body as professionally as possible. Her teeth began to rot after she started having kids and nursing babies. I bounced into her room on an unexpected visit after work, she walked out from her bathroom saying she had just pulled her tooth after a particularly painful day at work. Following her wreck, Beth went to the ER. At this point, her skin clung to the bone. I have often, in my mind, compared the way her body wasted away to the bodies of those who suffered in concentration camps – wasting slowly away with no help, she kept working to survive – a difficult but apt truth. She wasn’t able to eat or drink without getting sick. She told me that everything tasted rotten. An ER x-ray post-traffic accident proved she had no broken bones – so a week before she died, the doctors sent her home and told her to schedule an appointment with her primary care physician.

Later that day, she asked me if her neck looked swollen on one side, and I said it did. She asked, “Do I look terrible?” I told her she was beautiful. At some point – a moment that floats untethered in my mind along the timeline between the accident and her death – I asked her about her wishes if the boys were ever without parents. Beth said she would not let herself think about that because it was too painful.

On July, 5th, Beth went to work. Her boss had been trying to get her help with a doctor in a larger nearby town. She spent her last day at work between tasks with her head on her desk. Leaving for the day, she said to her boss, “I’m going home, feeding my boys, and putting myself to bed.” At 3:00 a.m. Bryce, her middle son, heard her throw up in the bathroom – a sound he said was more and more common to hear coming from her room at night.

When I arrived at Beth’s house that terrible July morning, my mom and stepdad were in the living room. The boys were in their rooms. The house was silent. Mom told me that Beth’s boss had called numerous times that morning as she was late for work, which was unlike her. Beth never answered her boss’ calls, so she drove to the house and rang the doorbell, waking the youngest son (age fourteen) from sleep. He answered the door and soon went to retrieve his mother from her room; he returned to the door saying, “I can’t wake her up.”

When I entered her bedroom, she lay on her side, with her back to me. I fell onto the bed beside her looking at her face. Her eyes were closed, her mouth slightly open. Her arms were outstretched embracing Gerald’s pillow. Her feet were crossed at the ankle.

The coroner leaned back on Beth’s dresser, arms crossed, studying all that remained of Beth lying on the mattress. “Well, looks like Pancreatic Cancer to me – See, that photo of the woman in the license is not the same woman here. I tell you, my sister-in-law is right up there in the hospital, right now, fighting pancreatic cancer.”

Looking again at Beth, he said, “She doesn’t appear to have suffered.” Bryce (age fifteen) said, “Well, she suffered for the last eight months.” Pausing, the coroner continued, “I’m just gonna be honest with you, The State of Alabama doesn’t care about your sister. We don’t care why she died. If you want to know why you are welcome to pay for an autopsy. They are about $10,000 and I know a guy in Birmingham. Let me go get his card.” The coroner left the room.

After Beth had been lifted from her sleeping spot, placed on the gurney, and wheeled away, we sat silently in that awful house. While, Kaleb, Beth’s oldest son, boarded a plane in South Korea returning home from his first deployment in the army. Beth was supposed to pick him up from the airport that evening.

Two days after she died, a doctor’s office from Dothan, a nearby town, called to confirm her appointment the next day. I let them know she died in a message following the recorded instructions and tone that indicated to start talking.

No one called back.

Now one year and five months after my sister’s death, the question that I have lived with every day is what happened to her? Beth was a hardworking, tax-paying Alabamian: how could Alabama not provide the most basic access to healthcare to help a tax-paying citizen? How do we reconcile as a society, as a state, as a people that the barrier standing between poor Alabama and healthcare isn’t a stranger, isn’t an enemy from across the ocean but one of our own, an elected official? How much more terrifying is it when the enemy isn’t the other but instead, the self?

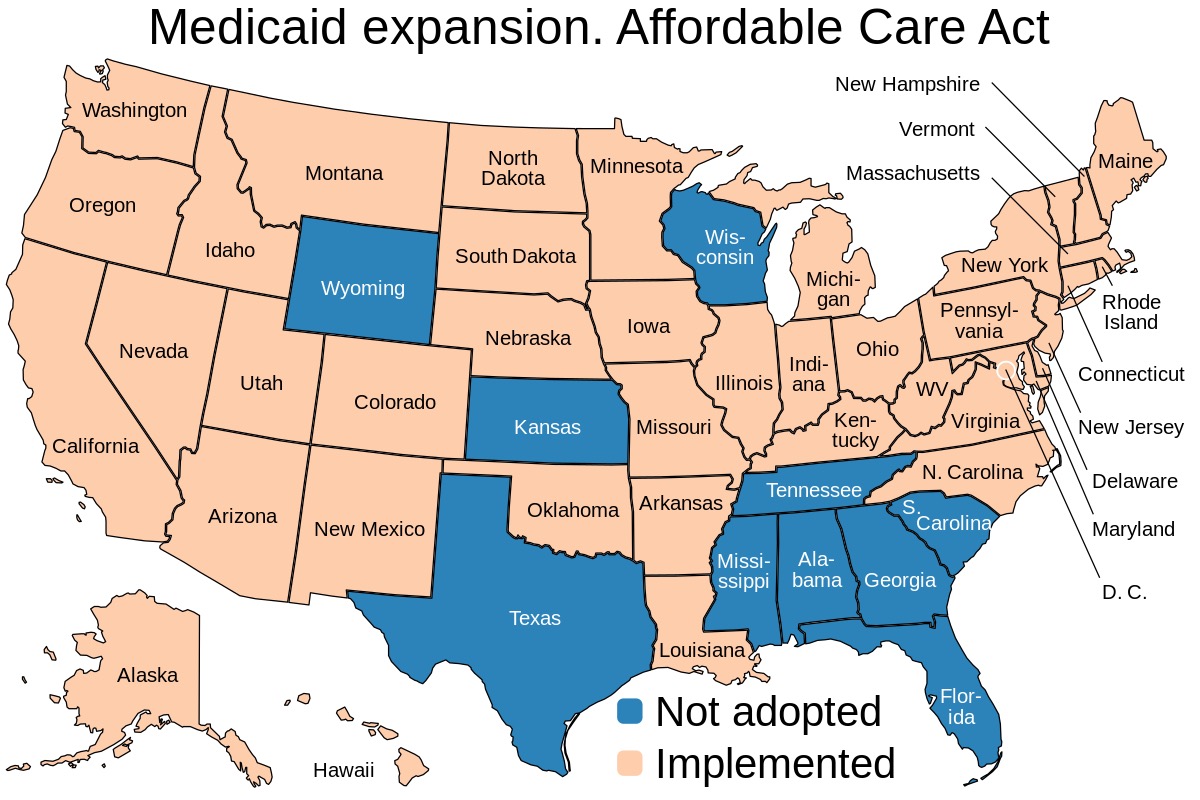

Healthcare is so often made into a political issue when the reality of it is a matter of life and death. Alabama’s current governor, Kay Ivey, continues to refuse Federal tax dollars that will pay 90% of the total cost of expanding Medicaid in Alabama. Kay Ivey refuses to allocate Alabama state tax dollars to make up the 10% of the remaining cost of Medicaid expansion. This does not stop Alabama taxpayers from paying for Medicaid expansion—Alabama federal tax dollars fund Medicaid expansion in other states, just not in Alabama.

In states that have expanded, Medicaid Expansion has paid for itself in three years. Rerouting patients from emergency care facilities to general practitioners for long-term preventative healthcare will alleviate the chronic disease that is overwhelming the healthcare system.

How do we, as a state with a large faith community, live with the onus of abandoning the least of our community? Providing healthcare for all Alabamians would strengthen our workforce and is an affordable and simple investment of dignity and respect for all citizens. We rely on these vulnerable and valuable members of our society to build and repair our homes and refill our sweet tea mid-meal at the local restaurant. All bodies are worthy of dignity. All bodies require care. As Alabama continues to close hospitals across the state the healthcare problem is becoming everyone’s problem. Kay Ivey holds the power to change our healthcare system. Yet she refuses to accept Federal Medicaid funding while misappropriating Federal COVID money to build private prisons.

The state of Alabama has had more deaths than births in 2020, 2021, 2022 and is on track for the same record in 2023. As a cancer survivor, Kay Ivey must know the life-saving importance of access to healthcare. Poor Alabamians who fall into the Medicaid Coverage Gap are left to believe we are not worthy of medical care that can prevent or identify disease early enough for treatment. If this isn’t true, why won’t Governor Ivey accept the Federal money to provide healthcare for more than 340,000 Alabamians? What is keeping Governor Ivey from leaving a legacy of life-giving healthcare for all of Alabama?

To quote Alabama Arise: “Medicaid expansion would save lives and create jobs. It would extend health coverage to more than 340,000 Alabamians. It would boost our workforce. It would stabilize our state’s rural hospitals. It would address the prison crisis by strengthening community mental health and substance abuse treatment services. And it would pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the economy every year. It’s a bargain Alabama can’t afford to pass up.”*

Despite what the coroner said, Beth’s life mattered. She mattered to her sons and grandson. She mattered to her parents, grandmother, sisters and aunt. She mattered to me. Beth Fine was a fiercely loyal ally. She always fought for the underdog. Even as a child, she would take on blame and punishment for those she loved. She was an adored grandmother, a warrior with a hilarious spirit and a sassy approach to life. She deserved help, she deserved care, and she deserved to die with dignity. Our healthcare system failed her; it is failing us.

Beth’s middle child turned 19 in August 2023 and has now entered the Medicaid Coverage Gap. Must this brutal cycle continue?

If you fall within the coverage Gap or are a concerned citizen, you can take action to have your voice heard. Get involved in the Alabama Arise campaign to expand Medicaid, or write or call the governor directly.

Jenny Fine (b. 1981, Enterprise, AL) is a visual artist living and working in New Brockton, Alabama. She currently teaches as an online adjunct professor in the Department of Visual Arts and Art History at Florida Atlantic University and is the primary caretaker for her 92-year-old grandmother and disabled father. Based in the photographic form, Fine’s practice attempts to “reverse the camera’s crop” by returning space, time, and animation to the latent image of memory. Through a cross-disciplinary collaborative approach, Fine creates images and environments inspired by her rural southern landscape and her family’s stories.

To view more of Jenny Fine’s artwork, please visit www.jennyfine.com.